Balance, and finding balance. It evokes pictures of rocks stacked upon each other at the beach. It’s something of an ongoing search for time crunched people. How they can bring balance to various aspects of their lives? There are endless self-help books and articles to read about it, but plenty are still aggrieved about their lack of balance.

But surely balance is a choice? If you had the extra drink or the extra bowl of ice cream. If you signed up for the new car or bigger mortgage. They’re all commitments that might result in feelings you don’t want later. Hopefully it was all a conscious decision and there’s no need for regret. Just floating along and hoping for the best is no strategy.

Recently, the actor Adam Sandler was profiled in the New York Times for his new film Uncut Gems. Sandler has an estimated net worth of several hundred million dollars and he noted he has a dilemma, like the rest of us.

Sandler admitted that he had not had a Popsicle in a while. He studied the menu of frozen delights with the unhinged joy of a man who, at a later meal together, would force himself to order three scrambled egg whites, a bunless hamburger and pickles. As a middle-aged man, he’s concerned about his health. Being rich, he told me later, can buy you a chef or a personal trainer, but it cannot buy the self-control to not pound a whole thing of ice cream on the weekend.

And with unlimited resources you might imagine there’s a temptation to let things get out of control, but Sandler’s doing his best to keep things in balance and not just floating along.

Financially, it’s no different. Our portfolios first need balance and then a commitment to maintain that balance. One of the continually ignored areas of investing is rebalancing. It’s a bit above the media’s head and it’s not particularly exciting. As a result, they bypass it to focus on the next hot stock, sector or where they think the market is heading. Nevertheless, it’s a key part of portfolio management.

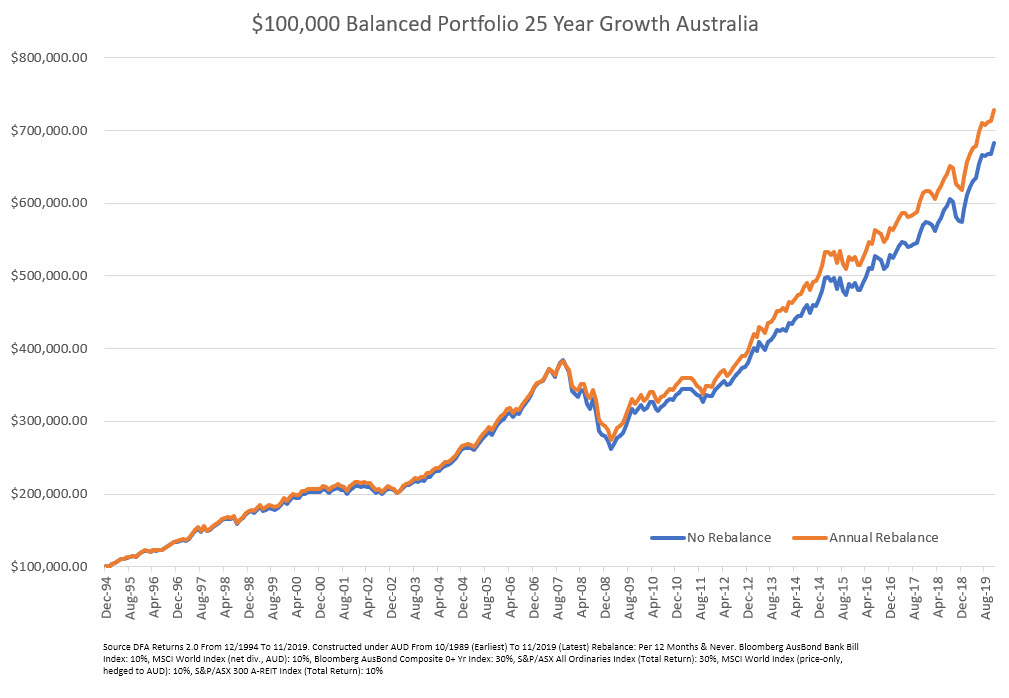

If we take a look at the effect rebalancing may have on a portfolio, here’s a chart of the last 25 years using a balanced portfolio with an Australian focus. 60% of its assets in growth and 40% of its assets in defensive. There are no contributions.

After 25 years an annually rebalanced portfolio has grown to $728,429 or an 8.27% annual return. While the portfolio left to float onward by itself has grown to $683,482 or a 7.99% annual return. This assumes no taxes or trading costs. In this instance it probably weights the case for rebalancing as a performance issue, but it’s not the reason to do so. If we take a look at a US based alternative over the same time frame, it’s a different story.

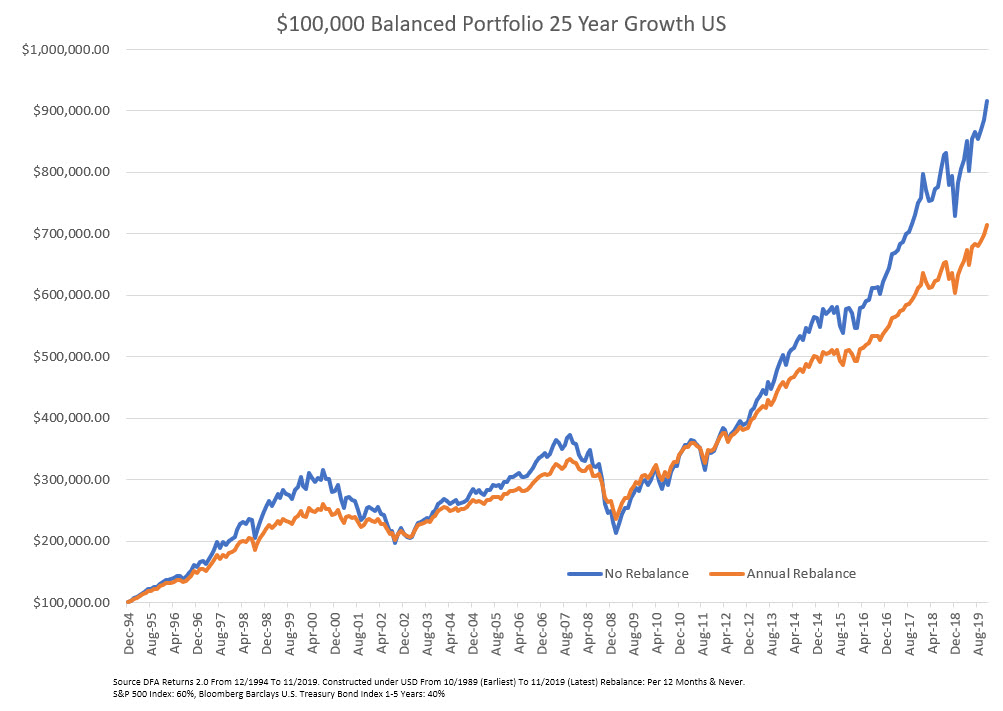

After 25 years the annually rebalanced portfolio has grown to $713,964, while the unbalanced portfolio has diverged significantly from its balanced counterpart, growing to $915,801.

Why the disparity? In this instance the Australian focused portfolio has more holdings. Excluding the small amount of cash, the holdings within the Australian portfolio have also seen returns within a tighter margin. Australian stocks offered the highest return at 9.76%, while Australian fixed interest offered the lowest return at 7.02%. Hedged and unhedged international stocks and Australian listed real estate returns fell between those two. Rebalancing managed to exploit variances in the returns and subsequent weightings in the more diverse portfolio.

In the US option, there were only two holdings. The US stocks returned 10.15%, while the fixed interest trailed at 4.03%. The majority of the return difference came after the financial crisis. Rebalancing this portfolio meant more money was moving out of stocks that relentlessly pushed higher, and into fixed interest offering historically low returns. However, the non-rebalanced option long ceased to be a balanced portfolio or even the portfolio the investor originally signed up for. It was overwhelmed by the stock side of the portfolio.

In short, the effect of rebalancing will be determined by the assets in the portfolio, their performance relative to each other and the frequency of the rebalancing. Rebalance every six months or two years and these outcomes differ again. So why do it?

Most of all it’s about controlling risk in a disciplined manner. Something we all have the ability to misjudge. Investors will sometimes battle their advisers about rebalancing and usually it’s about feelings.

Just 12 months ago we were in the midst of a serious correction. A year on and we’ve seen the strongest annual return since 2009. Both provoke strong feelings. The correction brings revulsion. Investors wonder why their portfolio tilted so heavily toward stocks and should they be selling out? A yearlong positive run brings euphoria. Investors wonder why the portfolio isn’t tilted more heavily toward stocks and should they be buying more? If an investor is two years from retirement, ahead of projections and their adviser says, “we’ve had a good run”, then it’s time to listen.

As Vanguard notes about rebalancing:

it’s important to keep in mind that the primary benefit of portfolio rebalancing is to maintain the risk profile of an investment portfolio over time, rather than maximize returns. In fact, if a given investor’s portfolio can potentially hold either stocks or bonds, and the sole objective is to maximize return regardless of risk, then that investor should select a 100% equity portfolio.

If an investor is prepared to let their portfolio drift wildly then they need to stop and consider their goals and their attitude to risk. If they don’t want to rebalance during good times would they prefer a 100% stock-based portfolio along with the volatility?

The arrival of the next 15% correction will likely provide them with the answer. A definite no. That’s why investors should never let their feelings during market movements drive their decisions. A commitment to rebalancing ahead of time keeps a portfolio where it should be.

It’s the easiest form of self-control we have.