They were the subject of much derision at the last federal election. Before you say the Labor party, no.

Electric cars.

What’s powering them (besides electricity)?

Batteries. Charge them up and away you go – hopefully for a few hundred kms. Most of the battery focus has centered on the lithium-ion battery. There’s no need to get too deep into various battery chemistries, but some of the minerals and metals required to make the battery are lithium, nickel, cobalt, manganese and graphite.

The race to manufacture the batteries has resulted in the construction of a significant number of battery mega factories around the world. According to Simon Moores of Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, a lithium battery consultancy, at last count there were 70 lithium ion battery megafactories in construction. By 2028 battery production capacity will potentially be able to power 23-24 million sedan sized vehicles.

Sounds exciting, especially for investors who want a piece of the action.

Where is the easiest place for investors to get targeted exposure to the electric car revolution? Car makers? Nope. They’re mostly boring dividend payers. Battery makers? Nope. Many are already integrated within chemical and electronic companies.

It’s exploration and mining companies.

If all goes to plan, there will be an increasing demand for all those raw materials mentioned earlier. They’ll need to be mined, or in lithium’s case, mined or extracted from brines. A lot of hype and a lot of stories. And a lot of opportunities for hyped up investors to lose their shirts.

How long before that happens? You might be surprised. We’re only in the early stages of this automotive change and there’s already been one boom and bust. A lot of investors are already walking around shirtless.

Firstly lithium. Keep in mind there is various lithium pricing because there are various sources of lithium. It can come from brines where salt flats are located. Most of the world’s lithium in this form comes from South America. Alternatively, it can come in hard rock form. Australia is the world’s largest producer of hard rock lithium.

Whatever price you’re looking at, it’s been on a consistent downward slide for lithium since the start of 2018. Why would this be? As always, same old story in mining. There’s a demand. Companies rush to build mines and fill the void. They fill the void (and some) with the end result of punishing themselves and their investors in the process. A story old as time, but one always forgotten during the boom phase.

In August, Alita Resources went into voluntary administration. Production at Alita’s Bald Hill mine in Western Australia lasted just over a year. One of the bigger (temporary) success stories, Pilbara Minerals, slowed operations at its Pilgangoora mine in WA. Pilbara also made a number of staff redundant last month and laid off contractors before embarking on a $91 million capital raising to get itself through the downturn. A year ago, Pilbara shares traded at 86 cents, at last check they were at 30 cents.

It’s a similar story across the industry. Investors in the big overseas listed miners, SQM and Albemarle have seen 50-60% losses over the past two years.

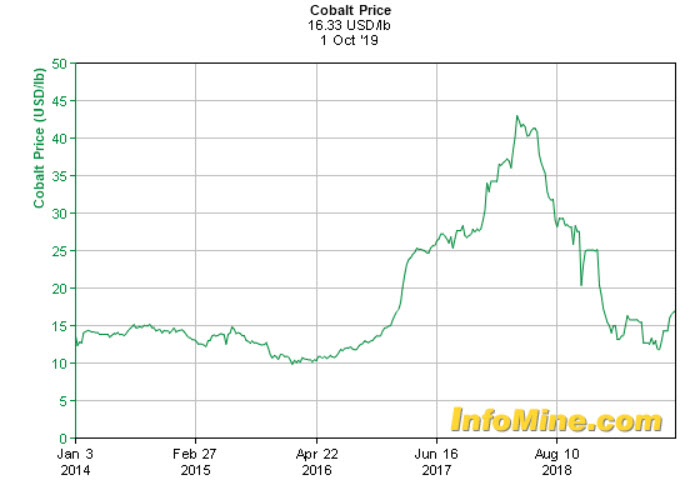

Cobalt was the other hyped story. It’s meant to be even scarcer than lithium. Investors started to think of the riches to be made for anyone who jumped on board. Where do you invest to get cobalt exposure? 60% of the world’s cobalt comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Swiss miner and commodity trader, Glencore, has a significant piece of that market.

Cobalt, like lithium, has proven to be another story of burnt fingers. However, unlike lithium, there’s been little in the way of new mine progress. The hype train pushed the cobalt price upward with plenty of explorers grabbing mining leases in the hope of getting lucky. If you want to see how well they fared, it wasn’t much different to the cobalt price. Up on hype and straight back down again.

In the DRC, two thirds of the population live on between $1-2 a day. A lot of cobalt is accessible by individual miners with hand tools. When the price rocketed, a lot of people in unfortunate circumstances had an opportunity to make some money. At the same time, Glencore increased its production. Suddenly warehouses in southern Africa were full of cobalt. Oversupply pushed the price down again.

Glencore has now halted production at its largest mine, Mutanda, and is also in a standoff with the Congalese government over mining royalties.

It’s always tempting to be on the lookout for the next great advancement. Speculators who can jump onboard early enough might make themselves a quick buck. They just need to know when to get out. Very few people picked the top in the last lithium and cobalt spike. Look on investment forums and you’ll find trapped investors who rode the prices downward now grasping for any piece of information indicating those prices might recover their previous highs.

As we regularly say, great stories don’t always make great investments. Long term, if the electric vehicle story is a winner, the gains from the car makers, battery makers and miners will find their way into the various funds a globally diversified portfolio holds. That ensures, as with every other sector and industry out there, an investor will capture some of the gains and be protected from the worst of the losses.