“el hombre perezoso hace el doble de trabajo.”

You might say this Spanish proverb is about the discouragement of a certain behaviour. In almost every facet of life we are encouraged to give our best and work our hardest. It’s something we see taught in school. When we go through our careers. Maintaining our homes, or if we’re involved in competitive recreational pursuits. Not giving our best will surely have consequences.

“The lazy man does twice the work.”

The belief is that more effort will bring its own rewards. In this instance, not having to do something twice becomes the reward. The message? Hard work is encouraged, laziness is discouraged, but laziness also becomes a penalty. Nothing wrong with believing this, except it’s not exactly universal. Occasionally the hard work mentality will encounter a vocation where a lack action and hard work becomes beneficial.

In what vocation could laziness be an advantage?

Investing.

Every year financial markets continue to work. In most years they distil the gains from capitalism and human progress into shareprice growth and dividends. As investors there is little we need to do if we hold a market-based portfolio. The best course of action is doing precisely nothing. Markets will move around, but historically they’ve reliably rewarded investors for their laziness.

Being a lazy investor should be a proud boast, but occasionally you’ll hear disparagement. Emotional blackmail from active managers and stock pickers. Accepting the market return is somehow embarrassing when you could be allocating your money to those investment managers that work hard and put in all the effort. Almost as if investors should be ashamed of paying lower fees for a more reliable outcome.

The lure of a “better outcome” is what we’re sold with active management. While this “better outcome” doesn’t come all that often, COVID was meant to be the big differentiator. The market plunge and the subsequent recovery was the opportunity for active managers. Money rotating through sectors faster than ever before would allow active managers to show their worth and leave the market in their dust. That’s what we were told.

Despite these bold proclamations from the active managers and the media who indulged them, when the dust settled, there was little sign that COVID helped their cause. All that hard work and it was the lazy market that again showed its worth for the investor who wants to think about things other than picking the next hot manager.

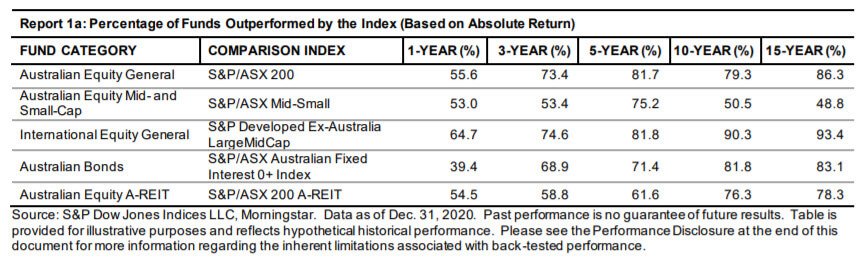

According to the 2020 SPIVA report, which keeps track of these matters, in every category (except bonds), less than half of active managers outperformed their benchmark. Once again proving, that when it comes to investing, the lazier you are, the better off you’ll be.

And as the years go on, the more damning the numbers become. In four out of the five categories the odds an active fund manager will be outperforming the market after 15 years are less than a quarter. In the international category you could argue active Australian fund managers are wasting their time even trying because the figures are so conclusively damning.

This is another challenge investors face because while it seems like a maths challenge, it’s again a behavioural issue. If someone has been a hard worker and believes in the value of hard work, they are faced with something that diametrically opposes what has worked for them throughout their lives. Embracing the importance of doing nothing.

This becomes even harder when there are temptations.

Around this time last year there was a small Australian fund manager garnering some news coverage for being one of the few who saw COVID’s impact on markets. They picked the top and sold out before the crash we were told. For an investment manager, having this feather in their cap is extremely valuable. The media will gush over them, then regularly call them up for their thoughts on markets: “the person who picked the crash now says…” This is all free advertising. It lures new investors to their funds.

We did a little digging on their two funds. We’re not going to name them because they are only a small manager. We also don’t want to get into the business of targeting one small manager when there are bigger offenders. As an example, the flagship global fund of a well-known Australian fund manager underperformed their benchmark by 5.6% in 2020. Yet the manager couldn’t bring himself to admit this when interviewed. In media he moaned the Australian dollar went against him and the fund was doing brilliantly – if you measured it in US dollar terms!

Such is the fragile ego of active fund managers.

But back to our crash picking friends, one of their funds focuses on Australia and the other invests internationally. First their Australia fund. Over the last 12 months they underperformed their benchmark by 4.1% before fees. They absolutely did not pick the top with this fund; it declined with the market and didn’t recover as powerfully as the market.

In their international fund, over the last 12 months they underperformed their benchmark by 1.3% before fees. In this fund they definitely avoided the worst of the sell off, but it mattered little because, as noted in one of the media articles congratulating them on their foresight, they expected another market sell off. As they sat in cash waiting for the opportunity to buy lower, the market began its recovery. The windfall of their successful forecast was quickly erased by an unsuccessful forecast.

Thanks to the articles written about their forecasting prowess this fund manager likely attracted a lot of new money from investors. And as is common in these situations, any investor who made the switch to the short-term winner promptly underperformed. Their fees? Between three to six times more expensive than their market equivalent! This is why investors always need to be sceptical about the benefits of active management, no matter how well it is promoted in the media.

Which brings us to another Spanish proverb.

“el gestor activo tiene que tener razón dos veces.”

“The active manager has to be right twice.”