Every year we’ll be confronted with a multitude of disasters. Sombre yes, but a fact regardless. Maybe they won’t affect us personally, but they’ll appear before us on the news and they should be pause for reflection.

Most show how relatively helpless we are as human beings. Earthquake, tsunami, volcano erupting, hurricane. Natural disasters aren’t preventable, however bridge collapses, dam failures, plane or rail crashes are all preventable to some extent. Here, human error or mechanical failure in various guises begins to play its part.

The aftermath of these disasters will inevitably be accompanied by questions. Depending on the outrage, they may start with who is to blame, but that’s just really the angry way of asking – could this have been prevented? Disaster stories receive significant attention, even long after the event where the focus often moves to preventative measures missed.

What’s much rarer or harder to find are disaster averted stories. Yes, they certainly exist, but they don’t capture the same attention or interest as when an actual disaster occurred and its lack of prevention. Arguably, it’s harder to quantify something unless you felt, experienced or witnessed it in some form. Dodging the bullet will never evoke the same feelings as actually being struck by the bullet.

Probably the most prominent disaster in many peoples’ living memory is 9/11. You probably couldn’t conceive a 9/11 style event before it happened, so the odds aren’t great you could adequately value its prevention, “could that really happen?” you might ask.

There were opportunities to prevent 9/11 from occurring, but a lack of cooperation between the FBI and CIA led to oversights. Had 9/11 been prevented, the news of the failed plot and how it was stopped likely wouldn’t get much attention. Maybe a story buried somewhere in the middle of a news bulletin for a single day. We’d likely never think about it again.

Today it’s all too obvious how valuable prevention would be.

It’s similar with investing. While sharemarket risk and volatility are all too apparent because we’re confronted by them on a daily basis, other alternatives that promise either guaranteed returns or stability may look like better options. Usually because it’s hard to conceive what might go wrong without a specific historical precedent to work from.

Any investor who put their money into an ostrich farm, a tree farm, a whisky barrel scheme, a forex ponzi disaster, mortgage debenture failure or bad investment property likely couldn’t visualise the worst-case scenario. If they had, they wouldn’t have committed in the first place. They may have briefly considered the risks, but likely didn’t consider any worst-case scenario because many alternative investments offer an illusion of stability. Crucially, in some minds their isolated nature and lack of history provides as much a case for, as against them.

Stability offers an impression it will prevent loss. It also alleviates the vexed issue of having to deal with the emotions and feelings that equity markets provoke. The stable investment problem recently reared its head again in the US with tree farms planted in the late 80’s and early 90’s.

If you work and you didn’t want to put all your money in the stock market, you’d buy 40 acres and plant trees and they’d be ready to cut by the time your kid went to college,” said Skip Stead, a timber broker in Lincoln, Ala. “It’s like a 401(k).”

What happened?

A glut of timber has piled up in the Southeast. There are far more ready-to-cut trees than the region’s mills can saw or pulp. The surfeit has crushed timber prices in Mississippi, Alabama and several other states.

A lot of retirements are now being reassessed – at retirement time. On a personal level that’s a disaster. And how did this happen?

At the depths of the 1980s farm crisis, when prices for agricultural commodities plunged, the Reagan administration launched the Conservation Reserve Program. Starting in 1986, it promised farmers annual payments of about $30 to $50 for each acre they planted with trees or grasses.

Now what might have prompted a bigger interest in timber as a long-term retirement proposition in the late 80’s?

On Wall Street, when things decline, you tend to remember. When things decline a lot, you remember the date. Oct. 19, 1987 is one such example. The biggest single-day stock market collapse in history—a 23 percent drop—rendered once-trusted ideas useless and redefined the financial landscape for market professionals.

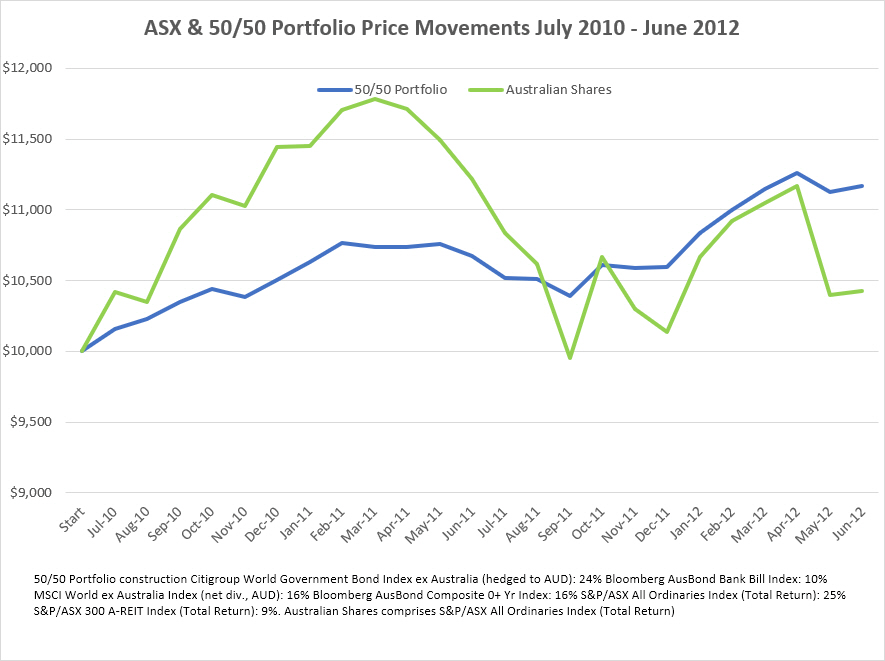

We’ve talked multiple times about the Nant Whisky scheme with its guaranteed 9.55% per annum return if you locked your money up with them for five years. It may have seemed like a worthwhile idea at the time. Interest rates were falling leading up to Nant starting to get attention in mid-2012. While the previous two years on the ASX weren’t particularly rewarding, especially given an 8 month double digit correction. A 50/50 portfolio offered reasonable returns, but the media doesn’t give updates on 50/50 portfolios each night.

How an investor is feeling at the time will inevitably play a part in their decision making when investing. Investors will be influenced by market movements that precede their decision. Risk feels heightened when the market moves around, even more so when it falls. It surely makes sense to gravitate to stability?

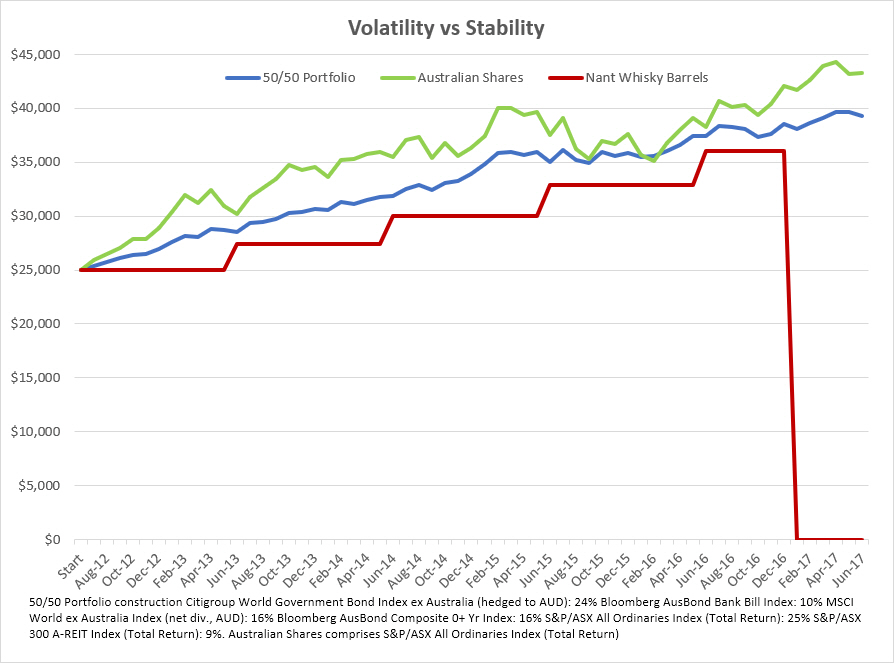

And after two years of sideways volatility, which included a double-digit fall, the ASX forged a more consistent path upward between mid-2012 & mid 2017. The return was 11.60% per annum, while a 50/50 portfolio returned 9.45% per annum – almost as good as the hypothetical Nant return.

Of course, Nant’s return is hypothetical because in early 2017 Nant fell into a heap and that stable return fell to zero with the initial $25,000 investment evaporating. Losing money like that is a disaster. Ignore the urge to compare with larger disasters on a wide scale, on a personal level it’s an emotional and financial disaster.

To prevent disaster, we need to know and understand a disaster is possible. Having someone on hand to critically assess risks is the best way to do that. Investors will always gravitate towards the promise of stability because it alleviates the issue of dealing with their emotions, but investment stability is an illusion – there’s no reward without risk.

The best form of stability an investor can find is working with someone who uses evidence to formulate an investment philosophy. It comes with the admission the future is uncertain, but there are factors that generate returns over time. Promoters of alternatives will always point to market volatility to play on emotions, but they don’t have history or evidence on their side and when their stability inevitably evaporates – disaster.

All too preventable.