One of the staples of investment media and stock picking newsletters are the ‘if you had invested…’ stories.

The writer will pick a well-known stock, go back to a point in time (usually the IPO) and inform us how many millions we’d have today, if only we’d invested a specific dollar amount into that stock. It’s meant to make us feel like buffoons. Why didn’t we jump aboard a stock than now seems completely obvious in hindsight?

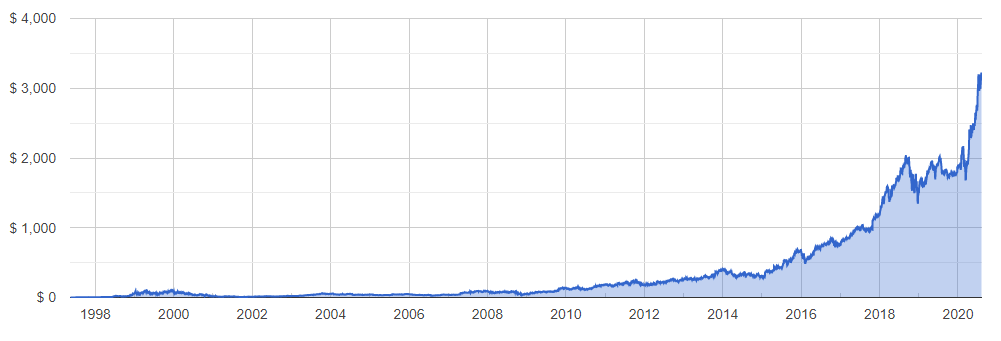

There’s even a website dedicated to the concept. Stock Time Machine. This tracks some of the largest listed companies in the US. Put in a date and see how much a stock would have grown. One of the favourites is Amazon. If you’d invested $1,000 USD at the IPO, it would be worth $1,617,426.4 by the first week of August 2020.

If only!

Amazon chart since May 1997 IPO

The blunt term for this is financial pornography. Besides making us lament missing the last big winner, it attempts to get us excited about identifying the next big winner. For the investment media, these stories are repeated regularly because they draw a crowd and the crowd sees their advertising. For the stock picking newsletters, it’s bait. They’ll lead in with the tale of the stock that gave a 10,000% return, before switching to the stock they’ve identified as having the same ‘explosive growth potential!’ Sign up to their newsletter to learn about the stock.

Survivorship bias gives the impression this is very easy. They hide the reality. They never furnish you with the thousands of other stories. The ones where that $1000 invested into another company is now worth $500, $200, $50, or nothing.

There are also never any faces behind the success stories. It’s just the stock performance. This makes it seem more unlikely, but there is a reason. Wealth and money are often private affairs. It’s why if you see someone in the media talking their investment or property success, they’re promoting something. Usually their own business. They are trying to acquire customers with themselves as the lure.

But someone must have done this, surely? Been there from the start. Rode a stock for 20-30 years. A few thousand dollars, to hundreds of thousands. Even a million?

Yes, it does happen. We’ve seen it. And can pose problems.

If an investor has hooked into several hundred thousand dollars (or even a million) for very little effort, it may seem like a good problem to have. But money being money, the mind does its best to complicate it.

Such holdings come about in various ways. You may assume some level of genius, but it’s more likely a disinterested investor who unwittingly went for a ride. It may have been a one-off tip and one of the few shares that person ever invested in, they now take pride in the holding. It may have been an inheritance and the stock now holds extra significance.

This one stock has never done this person or their family wrong. This one stock now constitutes 50%, 75%, maybe 90% of their wealth. What should they do?

Sell! Or make a plan to sell tax efficiently as possible.

If only it were that easy. To the dispassionate observer or potential adviser, this is the investor’s winning lottery ticket yet to be cashed. For the investor who bought the stock, they may have emotionally entered into a relationship with the company. To the investor who inherited the stock, this is no longer an investment, but a family heirloom. The prospect of a sale stirs an incredible amount of emotions.

For the investor who bought the stock, they can only see the good. There are twenty or thirty years of compounding. Wealth upon wealth. For the investor who inherited the stock, it feels like custodianship. They’re holding a legacy.

Both are natural reactions, but an investor in such a situation needs to acknowledge the anomaly that has occurred. Their experience is a rarity. Very few people will ever see similar happen. Very few people will ever find the stock, even fewer will sit on it for decades. Being able to move on from this success to then protect the wealth becomes a two-part thought.

Concentration can generate large increases in wealth.

Diversification is what maintains wealth.

For the investor who bought the stock, it owes them nothing and they owe it nothing. For the investor who inherited the stock, they are not a perpetual custodian who guards over the stock. The company is under the stewardship of a board and management team. Nothing the investor does will have any bearing on the company.

What if the stock continues to go up and a more diversified portfolio doesn’t perform as well? This is a decision made purely on risk. The correct decision can never be based on the outcome. To have an enormous percentage of someone’s wealth tied up in one company is inviting trouble. The investors need to disassociate themselves from the company and understand they are now custodians of the wealth it has generated. That wealth will still exist independently of the company.

For the inheritance, the investor may think that Nan, Pop, Mum or Dad would be rolling in their graves if the stock was sold. They would be rolling in their graves if the wealth was lost.

Great companies don’t always stay great companies and they don’t always stay great investments. We mentioned Exxon last week. In the late 2000’s Exxon was the largest company on the S&P 500. Today it’s not even in the top 30. Since peak, when it was valued at over half a trillion dollars, Exxon has lost 65% of its value.