If you have even a passing interest in films, you’ll probably know the names Robert De Niro and Al Pacino. Both have been mainstays of the film business since the early 1970’s, with the pair acclaimed and awarded for their performances dating back to that decade.

Despite their long resumes and regular appearances in gangster and crime films, the pair have only appeared onscreen together in the same film twice. First in the exceptional ‘Heat’ (1995) and the terrible ‘Righteous Kill’ (2008). Both appeared in The Godfather II, but never appeared together onscreen. De Niro played a younger version of Marlon Brando’s character in flashback scenes.

Well into their 70’s, the pair have again collaborated in ‘The Irishman’, due to be released later this year. Spanning multiple decades, The Irishman tells the story of mafia hitman, Frank Sheeran, who claims he was involved in the disappearance of Union leader, Jimmy Hoffa.

Instead of casting younger actors to play De Niro and Pacino’s characters in flashbacks, the filmmakers are using CGI to make the pair look young again. It’s exciting that technology might be able to wipe years off De Niro and Pacino’s faces to make them look 40 or 50 again, but they’d probably admit, despite their youthful appearances in The Irishman, their cognitive function isn’t what it was back in their 40’s and 50’s.

As De Niro said in a 2013 interview, “it sucks getting old.”

Harvard Professor David Laibson is someone who has studied the cognitive implications of getting old and why it might ‘suck’. Laibson, along with Sumit Agarwal, John C. Driscoll, Xavier Gabaix studied a database that measured credit behaviour across ten areas, such as credit cards, mortgages, auto loans and their optimal usage.

The sweet spot for optimal usage of these financial products (ensuring the least in fees and interest were paid) were from consumers in their early to mid-50’s.

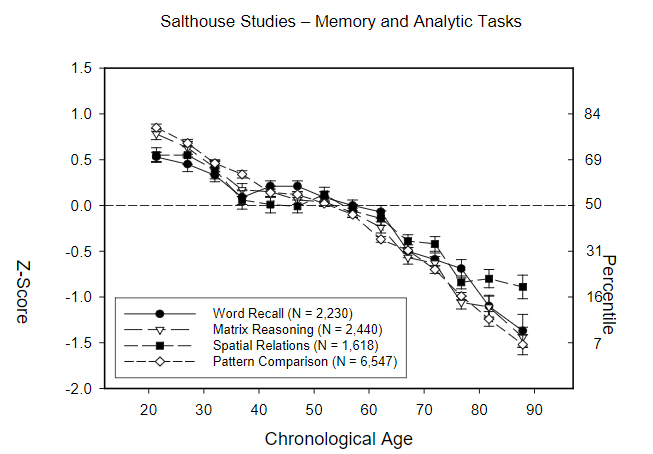

This aligns with work from Timothy Salthouse, which shows fluid intelligence is at its peak in a person’s 20’s and 30’s, almost a standard deviation above mean, and slightly above mean in a person’s 40’s and 50’s before a swift decline in the late 50’s onward.

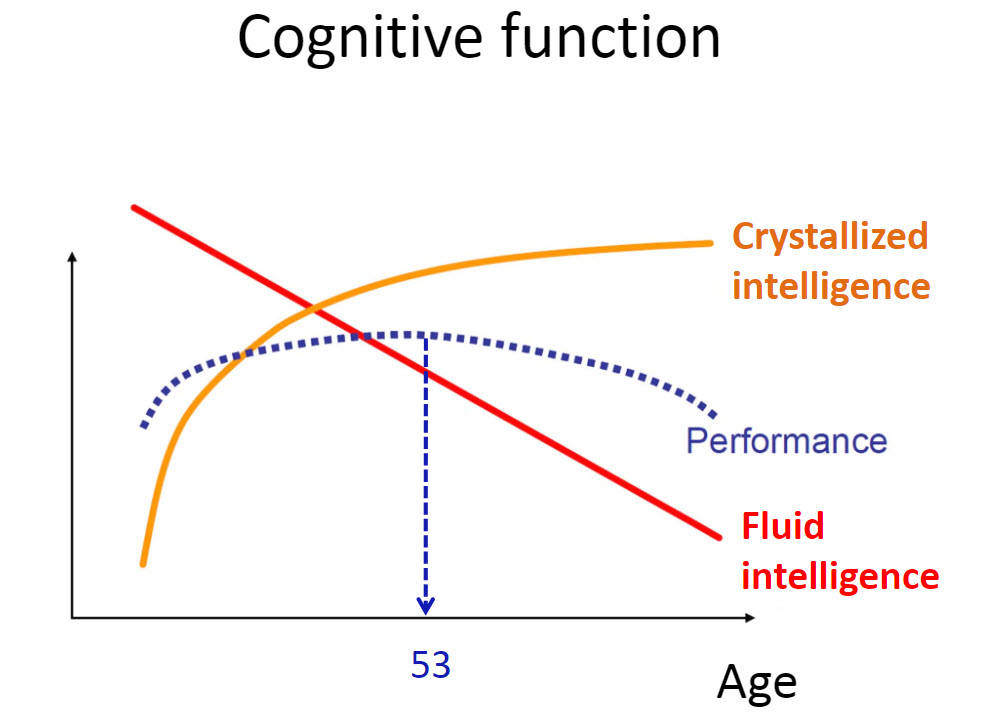

Don’t be too disheartened if you’re past your mid 50’s because these are measures of fluid intelligence. This is the ability to adapt and solve problems in new and differing situations without the need for pre-existing knowledge, it’s known to peak in a person’s 20’s. In contrast, crystallized intelligence is the ability to use already acquired knowledge and this continues to grow.

Experience does bring wisdom, but declining fluid intelligence begins to be a drag on our cognitive abilities in our mid 50’s, as this chart from Laibson shows. Fluid intelligence is an ever-declining asset, while crystallized intelligence continues to tick up, but the sweet spot where both combine for peak cognitive function is 53.

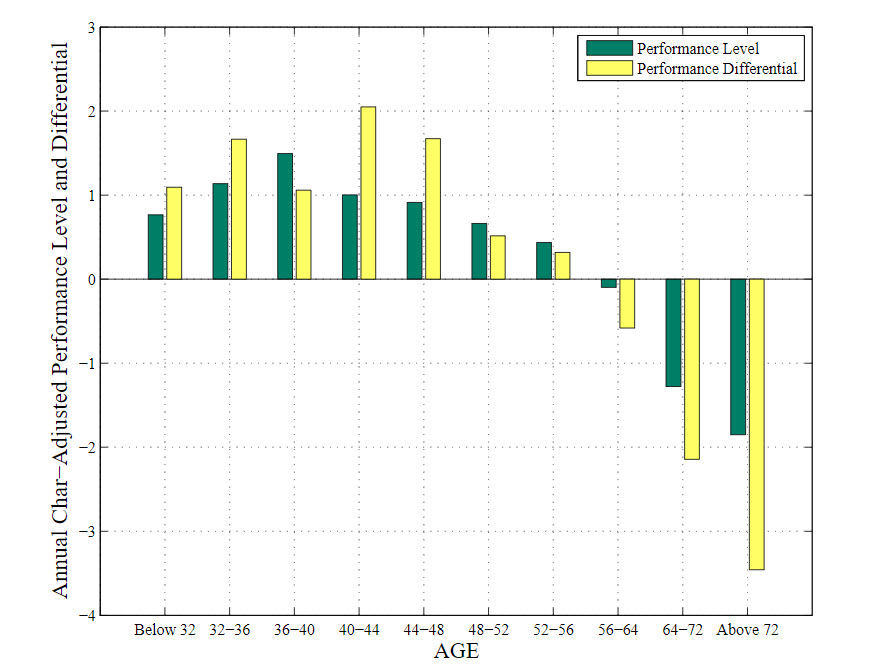

Further evidence comes from George Korniotis & Alan Kumar, who studied the investment trading accounts of 62,000 investors in a 2007 study. Note the mirroring of the Salthouse studies in age related performance decline.

As the pair said in their study:

we find that older investors earn about 3–5% lower returns annually on a risk-adjusted basis. Collectively, our evidence indicates that older investors’ portfolio choices reflect great knowledge about investing but their investment skill deteriorates with age due to the adverse effects of cognitive aging.

It’s not uncommon for financial advisers to see elderly self-directed investors in a pickle. Why would these older investors keep persisting for so long without seeking a second opinion? There’s one thing that doesn’t decline as we age – confidence.

A study by Michael Finke, John Howe and Sandra Huston found that while financial literacy declines around 2% a year over the age of 60, the confidence we have in our financial abilities does not decline at all. As it’s a gradual process, this is probably not surprising. Firstly, if we’re optimists we’re more likely to believe it won’t happen to us and secondly, we’re more likely to believe we’d recognise any decline.

Though as Professor Laibson says no one wakes up one morning and says “You know what? I’m losing a lot of cognitive function.”

If all this seems grim, it’s not. Most of the best financial decisions revolve around not making mistakes. Having a trusted second set of eyes on our affairs is the best way to avoid mistakes. It’s also a way to avoid any cognitive overload. If you’re mentally drained in another area in your life, your financial decision making may not be optimal.

The primary benefit of using an adviser is they have processes in place to manage a portfolio while removing cognitive and behavioural biases that can cause mistakes. They have experience dealing with people across various age groups and can recognise age related needs. They regularly deal with government, fund custodians and insurance companies, which can be some of the more trying financial related endeavours.

We often have clients remark to us, ‘we’re glad you’re on top of this because it would probably beyond us.’ And that means not only are the chance of mistakes likely minimised, they have the ability to direct their energy and focus towards something other than money.

If you’ve been working with an adviser, this probably isn’t news. If you haven’t, there’s never any shame in asking for help.

While the magic of CGI can make our faces 30 years younger, it’s the value of an adviser that can ensure our financial lives are evergreen.