There are some angry retirees around Australia right now. Labor’s plan to rescind franking credits from those who haven’t paid tax has seen impassioned speeches at public hearings, angry letters to newspapers, and media profiles where the aggrieved quote how much they’ll lose from the changes.

It all must be very confronting if you’re suddenly faced with losing a third of your income. Especially when you’ve left the workforce. As advisers we can understand the frustration, but our job is quite often delivering hard truths and telling people what they don’t want to hear.

We’d prefer it didn’t happen, but we’re not going to discuss the politics of the issue. Nor the winners and losers or the perceived unfairness. All that will be continually done to death in the media and political circles. There’s no need for another opinion here. Set all that aside for a moment because as financial advisers there is room for where we think there is a problem.

This is a very good example of an advice gap.

What is an advice gap? We’d define it as people who could benefit from quality financial advice, but still choose to plough on without it. The reasons can be many and varied, but often it relates to some sort of skepticism relating to the value. Sooner or later that skepticism and the ensuing gap may prove costly.

Take any of the letters to the newspapers, the responses to online articles or those who’ve been profiled in the media angry about the changes. They often make mention of ‘carefully planning their retirement’ or ‘making plans in good faith’. This may be true. They may have spent hours looking for the best way to design a portfolio for retirement. They may have settled on a strategy that satisfies their requirements and they may have implemented it.

Careful research and planning doesn’t automatically mean correct research and planning. A strategy may work for a while, but it doesn’t mean a portfolio built upon that strategy will be robust enough to serve a retiree’s needs and doesn’t mean their strategy is the correct one to navigate a multi-decade retirement.

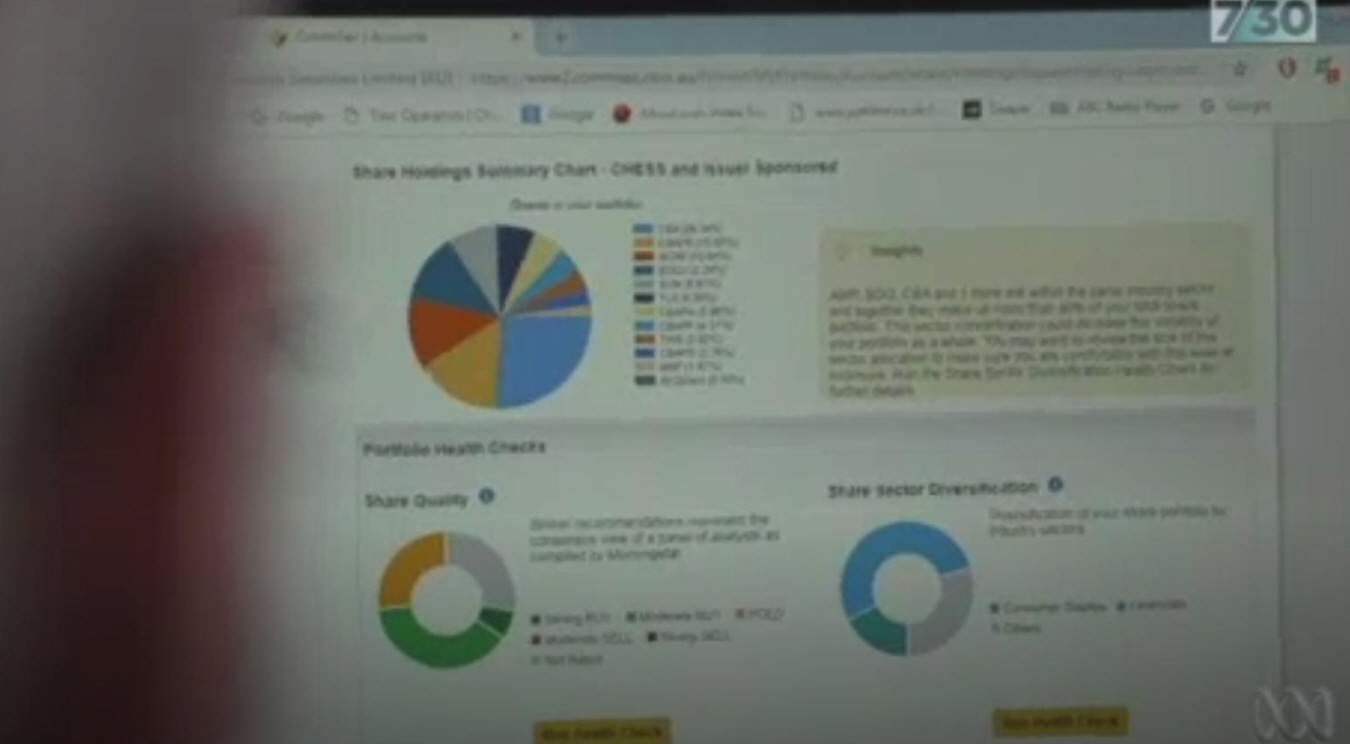

This week the ABC’s 7:30 program featured a story on the franking credit debate. The program interviewed a retired couple who were frustrated about the potential changes. In one part of the story they were shown looking over their portfolio on their computer. Above is a screenshot of that moment.

It takes an eagle eye, but you can make out their portfolio construction. There 12 holdings with 11 identifiable, the ‘other’ comprises 0.03% of the portfolio, which is not significant enough to factor in. Let’s say 11 holdings, seven are shares: Commonwealth Bank, Woolworths, Bank of Queensland, Suncorp, Telstra, Treasury Wine Estates and AMP. In addition, there are 4 Commonwealth Bank hybrids.

According to the sector diversification donut in the bottom right corner, around 70% of their portfolio is concentrated in two sectors – financials and consumer staples. Commonwealth Bank makes up 28% of the portfolio and that’s excluding the hybrids! It’s obvious this portfolio has had a sole focus on income. There’s a term for this: reaching for yield.

More specifically and more commonly, the phrase is applied to situations in which the investor chases higher yields without due regard to the added risk that he or she is usually incurring as a result.

In this case, the portfolio has seemingly been constructed around yield and maximising it by taking advantage of franking credit refunds. What could go wrong? Multiple things. Given the lack of diversification in the portfolio, it doesn’t take much to upset the apple cart. No matter how carefully these investors claim they have planned, this is a high-risk strategy and leaves them extremely vulnerable at a time when they’ve left the workforce. A common issue with self-managed super funds – they lack appropriate advice and as a consequence, diversification.

The top three most commonly held investments by size in SMSFs at the end of 2017 were Commonwealth Bank, Westpac and NAB. While the most widely held ASX share was Telstra, held by 50% of SMSFs. This was down from 55% a year earlier, likely down because of Telstra having cut its dividend only a few months earlier. Highlighting another issue with this strategy – business conditions can change, and your dividend darling is no more.

Qantas cut its dividend in 2010 and didn’t pay another until 2016. And from the pictured portfolio, we can only imagine these investors are smarting over AMP’s recent performance. The share price has fallen nearly 60% in the last year, while its dividend has just been cut 70%.

As we said when Labor’s franking credit changes were first announced last year:

The more a portfolio is concentrated on fewer assets to exploit specific advantages, the more likely a change in economic or business conditions, legislation or just technological advancements will torpedo a part of that portfolio.

And SMSF investors are prone to ignore diversification. From Vanguard’s Investment Trends SMSF report last year:

“the report continues to highlight a persistent potential lack of diversification in SMSF portfolios, with half of trustees saying that more than 50 per cent of their portfolio is invested in a single investment type – commonly direct Australian shares.”

While the SMSF Association last year found:

“Two-thirds of self-managed superannuation funds consider a portfolio invested in 20 shares to be well-diversified”

Which is either a sign of arrogance, ignorance or both. DIY investors, convinced of their brilliance, often have a way of ploughing headlong into a strategy they believe will pass the test of time. The longer it works the more bullet proof they believe it is. Then one day it stops working.

Those old enough to remember the late 80’s will remember the sky-high interest rates of the time. For those entering retirement, cash seemed to be the best place to be. In December 1989 the cash rate was 18% and many investors believed there was no need to look at any other asset class. Leaving your money in the bank could happily fund a retirement.

By December 1990 the cash rate was 12%. December 1991 it was 8.5%, by December 1992 it was 5.75% and by December 1993 it was 4.75%. Any easy retirement dreams that involved living off bank interest were obliterated in four years. The average of the cash rate since that point is 4.52%.

Any adviser with experience, or an eye to history, can point out these investor blind spots. They can also advise on a portfolio that aligns with an investor’s goals and is mindful of risk, ensuring the investor isn’t sitting on a ticking time bomb. However, according to the previously mentioned Vanguard report, over 60% of SMSFs don’t use a financial adviser.

We can only guess how many of that 60% are seriously impacted by these proposed changes to franking credits. Hopefully none of them are furiously arguing they’ve “carefully planned their retirement.”

Careful planning doesn’t have an advice gap.