One of the most well-known psychological studies ever done is the Stanford Marshmallow Experiment from the 1970’s. You’ve likely heard of it, know a variation of it, or have watched an interpretation of it somewhere in the media. Testing out the will power of small children or dogs can be entertaining. Dogs being tempted with food are a staple on social media.

In the Stanford experiment, the idea was to test the ability to delay gratification. In the first iteration, children were offered an immediate treat (cookies or pretzels) or the choice to wait 15 minutes and be rewarded with a second treat. In the second and more famous study involving the marshmallows, children were offered ways to distract themselves to see if it helped them delay gratification. Not thinking about or seeing the reward helped in the delay.

In the years following, participants were studied again and those who delayed gratification were said to score better on college entry scores, cope with problems and more easily deal with stress than those who didn’t delay. The study has also been called into question due to the number of variables that may factor into delaying gratification. For example, children from more affluent households may have a different experience with consumption than children from less affluent households and be more able to delay gratification.

Why bring up the marshmallow experiment? You might say Australia has been running its own marshmallow experiment recently, in the form of early superannuation release. At last count withdrawals were pushing $30 billion. For some, it may be alleviating the pressure of financial constraints thrust upon them by COVID-19. For others not eligible, it’s running a potential gauntlet to grab the marshmallows now, instead of waiting for more later. The ATO has been huffing and puffing on penalties, yet we’ve heard of no action.

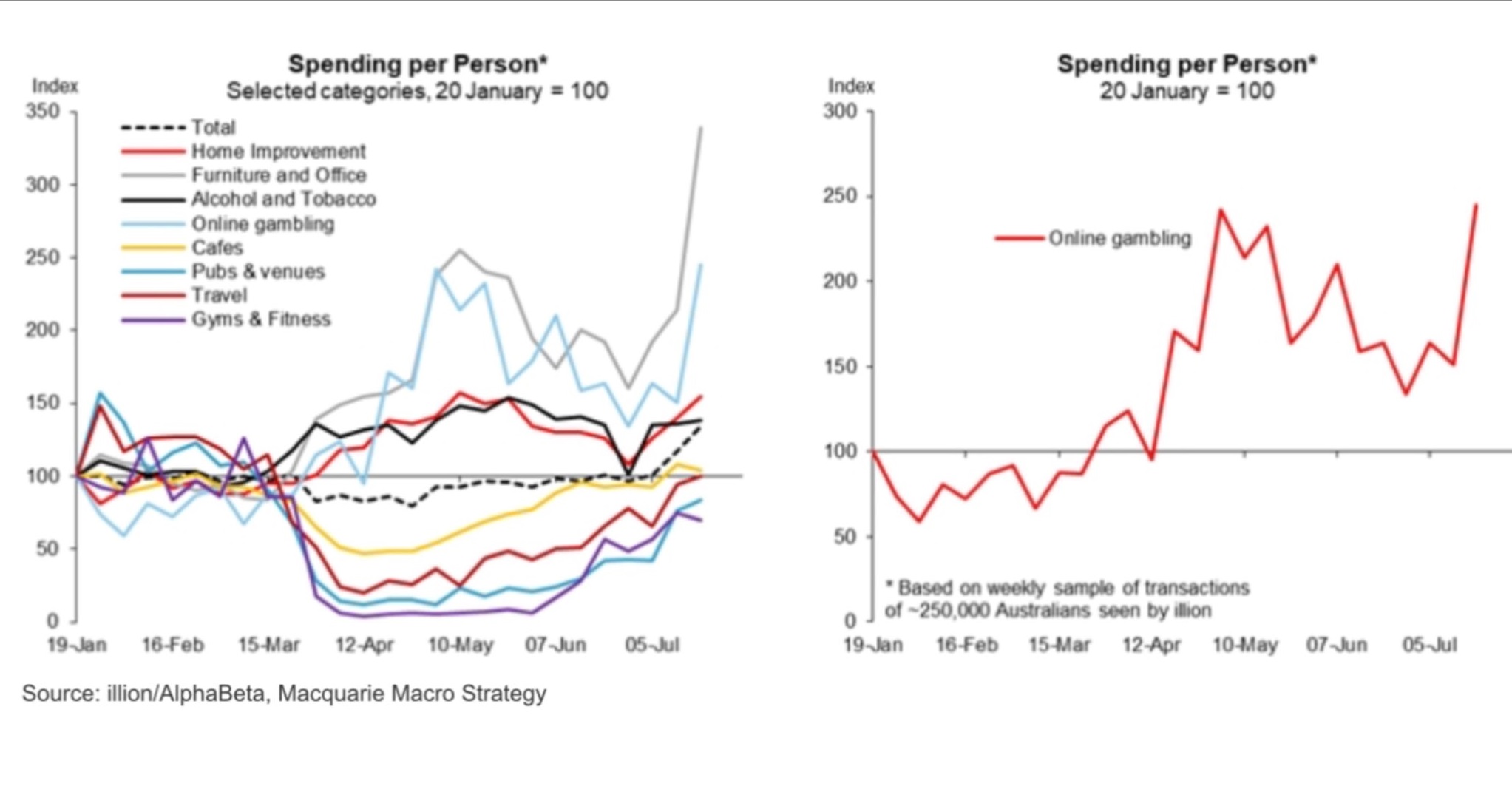

There have been various anecdotal stories of people pulling $10,000 from their superannuation last financial year and gambling, day trading, buying toys like go-karts or getting cosmetic surgery. There have been media stories about several of these decisions. And while a story in the media should only be considered representative of the person featured, one thing is true, spending on online gambling is up 2.5 times since the beginning of 2020.

Above is a chart of Australian spending per person in 2020. It’s compiled by data consultants AlphaBeta. Note the chart to the right, this is online gambling spending in 2020. You’ll note it spikes twice. Once after the first superannuation early release in April, then again after second early release after July 1. Draw your own conclusions.

The easiest explanation? From a 1994 study into windfall gains. A publishing company held their annual conference at a hotel just as a university had purchased one of their texts to be used in a course. Because there was no one person responsible for the sale, the whole marketing staff were surprised with a $50 bonus when they arrived at the hotel. Near the hotel was a casino…

Nancy, once of the salespersons spent her entire $50 there, as did nearly everyone else. She later said how disappointed she was with her own behaviour: “If I hadn’t been given the $50, there’s no way I would have spent a dime at the casino. There are plenty of things I could have used the money for. Why did I waste it?”

Some superannuation money won’t be treated like regular savings. It will be considered a windfall. The other concern? Superannuation may be seen as something to dip into regularly. The reality is some people don’t appreciate superannuation until later in life. Until then, it’s considered a waste of time.

We’ve heard a lot of nonsense over the years about superannuation. One of the favourite conspiracy theories is the government will one day confiscate it, so you’re better off in control of it. This one has popped up again recently. It’s an interesting thought because the government can afford its own army and possibly do anything it likes. But here’s another thought: there are over 2 trillion dollars sitting in bank deposits in Australia (individuals, businesses, charities). Why would anyone believe that superannuation is more likely to be confiscated than bank deposits?

Both thoughts are equally as ridiculous, but prominence and emotion have people believing one is a possibility.

Bank deposits are rarely discussed. They have no emotional resonance because no one debates their need or existence. They are of little interest in the way of discussion. Superannuation is the opposite. Media commentators, lobby groups or politicians always have a suggestion to amend, adjust it or do away with it. Funds are spending to tell us how good they are, or they are under fire for fees, insurance, performance etc.

At the core of this issue is an ideological war. The Liberal party doesn’t have a high opinion of superannuation. They didn’t create the structure. Worse, the largest super funds have ties to their mortal enemies, the unions. Unfortunately, it leads to the superannuation system to being a thing of conflict instead of a vehicle focused on the interests of retirement savers.

Are some of the industry funds as pure as they like to claim? Nope. Many aren’t as cheap as they portray themselves to be. They take bigger risks than they’re willing to admit to game performance tables. Dealing with them at times can be like pulling teeth. Is it cause for knocking the whole thing down? Nope.

The concern is some may see this crisis as their big opportunity to wreck the system. In this instance, offer people a taste of marshmallows and they’ll likely want more. “Why can’t I have all my superannuation? I need or want it now?” Australians aren’t exactly known as savers. Before the pandemic hit, our household savings rate was trending down towards 2%. Thanks to political parties of all stripes prioritising real estate, prices for shelter are stratospheric. They’re matched by stratospheric household debt levels.

Continually releasing super also fills another need, the government now wants people to spend. If people are seriously indebted and in a terrible economy, they’re unlikely to release the purse strings. Give them a sugar hit and they might change their minds. Years of bipartisan property pumping has left a highly indebted section of the population now exposed to recession. How do you get these people to spend over the next few years? Kick the can down the road and have them continually access their retirement savings. And if everyone else who doesn’t need the money also takes it early, even better for your economic figures!

But what is their plan for retirement? Forced saving and investing covers a population almost averse to the concept. The whole purpose of saving and investing is to offer options at a later date. Money buys time. Two numbers are particularly prominent when planning for the future: 60 and 67.

From July 1, 2024 superannuation preservation age is 60. From January 1, 2024, no one qualifies for the age pension unless they are 67. It’s a long time if a person is struggling without work in later life. There has already been an attempt to move the pension age to 70. For some people, yes financial concerns will be extremely pressing over the next few years. For others, they don’t need a free invitation to raid their retirement savings before they understand their true value.

We will all need a few extra marshmallows at a later date. The government would do well to recognise it.