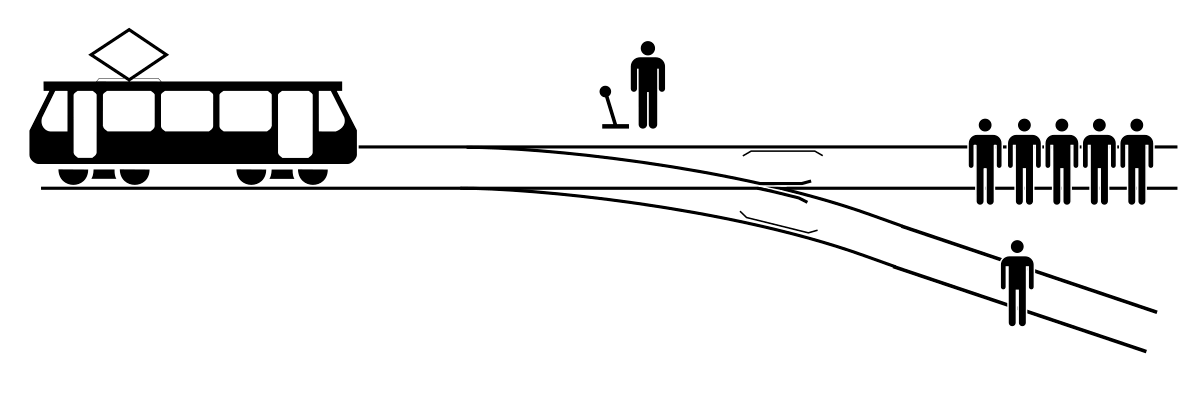

You’re out walking with your dog near a railway track. Behind you there’s a rumbling noise. Thundering down the track is a trolley, looking up ahead you can see the trolley is headed for a bridge with five workers on it. They will either be run over or jump to certain death. Beside you is a large switch. If you pull the switch, you will divert the trolley to a second track and another bridge. Only this bridge has a single worker on it who would face the same fate as the other workers.

What do you do? Pull the switch and save the five workers, dooming the one worker? Or take no action, saving the one worker, but dooming the five?

This dilemma which has many variants is known as the trolley problem and was introduced by philosopher Phillipa Foot in 1967. It poses a moral dilemma of choice when neither outcome is palatable. It might be a dilemma worth considering in the current climate of ESG investing. If you need a refresher, ESG stands for environmental, social and governance. The general consensus is ESG investing is about making more ethical choices with your investment dollars.

If we are to apply the trolley problem more effectively to ESG investing, maybe a more appropriate scenario is seeing the trolley heading toward the bridge with five workers, but you don’t have a clear view of the other track you can divert the trolley to. Do you believe your current portfolio is on the track to do harm? Could making a switch possibly offer a more palatable outcome? What would pulling the switch mean?

Many investors are rushing to join the ESG investing movement. As you’d expect, there’s no shortage of fund managers rushing to cater to these investors. History has shown if the investment industry thinks they can flog you hot idea, they’ll flog you that hot idea. If an investor is serious about ESG they may need to ask questions. As an ESG investor are you solely attempting to avoid particular sectors? Do you believe your investment choices are a force for good? Have you given yourself enough time to consider all the evidence?

Clarity comes with information, but what if the information makes things more clouded? The investment industry pushes metrics and stats to highlight ESG credibility, but for the average investor who is expected to process and accept them, what does something like a 0.00% MSCI – Oil Sands rating even mean? Quite often it’s a direction to check the small print.

Let’s take a look at a major ESG index which many funds will have their basis in. The FTSE Developed ex Australia Choice Index. To get a clearer picture of what ‘choice’ means, it was formerly known as FTSE Developed ex Australia ex Non-renewable Energy, Vice Products and Weapons Index.

Firstly, it’s an index of major companies outside Australia, but no fossil fuels or nuclear energy. No booze, smokes, punting, or naughty entertainment content! And no weapons. There’s also a screen on conduct related to controversies. As an investor, if those are the things you wish to exclude from your portfolio it seems like a good list. The question remains, is the title enough?

In our experience talking to investors about ESG, it’s more acceptance of the headline than any deep analysis of the holdings. If we were to use a food analogy, you might say it’s being transfixed by the ‘low fat’ label on the box without looking at the nutritional label. What you find in the nutritional breakdown may surprise you. In that instance the fat was just replaced with sugar.

The label on the box here? One manager brands their fund based on this index as ‘ethically conscious’. What does the ESG nutritional content look like?

The largest company in the index is Apple. The fourteenth largest company in the index is Samsung. No problem, you might own one of their products. Problem? Planned obsolescence. Remember when products used to last forever? Both Apple and Samsung have been accused of slowing down older smartphones to prompt users to upgrade. Both were fined in Italy, though denied the practice, while Apple settled a lawsuit relating to the issue for $500 million in the US.

Not only devious, but sending your smartphone to smartphone heaven earlier isn’t exactly a boon for sustainability.

Further looking through the holdings, and depending on where you sit, you might be confronted with more questions about companies with reputation, sustainability or ethical concerns. Facebook. Bayer. McDonalds. PepsiCo. Coca-Cola. Nestle. LyondellBasell. Du Pont. Nutrien. Dow Inc. Celanese. Lonza. This is far from an exhaustive list and notably the last seven of those names rank in another index: the Toxic 100 Water Polluters Index collated by the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI) at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

PERI tilts hard toward environmentalism in its worldview, but we are talking about ESG investing here. Maybe water polluters don’t fall under the remit of ‘Non-renewable Energy, Vice Products and Weapons’, but what if the fund is commercially branded ‘ethically conscious’? There’s something else an investor in this fund would have to reconcile and it gets back to our starting theme of railways.

There are no fossil fuel companies to be found within this index, but railways feature. The most notable are CN and CP or Canadian National Railway and Canadian Pacific. CN and CP both ship millions of tonnes of thermal coal. A lot of ESG investors are attempting to avoid coal. So as an investor you may have successfully excluded a product you’re looking to avoid, but not the transport infrastructure that ensures the product reaches the market.

CN and CP also ship crude oil. Between the pair, they both service the majority of oil & gas hubs across North America, shipping to export terminals and refineries. Being Canadian, they also service one of the more controversial oil fields in the world, Alberta’s oil sands. The province has had a real issue getting the product to market. New pipelines attempting to span Canadian provincial borders and the Canadian/US border have been incredibly divisive. This leaves rail as a key method of transporting oil.

Transporting petroleum products by rail can also be dangerous. Not only can derailments be environmental disasters, but a derailment in the Canadian town of Lac-Mégantic in 2013 killed 47 people after the rail cars exploded. The Lac-Mégantic disaster was not CN or CP, but CP had two oil derailments resulting fires in late 2019 and early 2020. In Canada, where the railways are listed on the sharemarket, both feature in many Canadian ESG, ‘social’ and ‘aware’ funds, as they are termed.

It seems contradictory to have such companies within ethical funds and it would be easy to take cheap shots at their inclusion. As with coal, oil is a non-renewable energy they are transporting, but on the question of danger related to the transport, both companies are looking for solutions. Canadian National has been developing a product called Canapux that turns extra heavy crude into sealed bricks for transportation. They don’t burn or explode and won’t leak if they land in a waterway. Canadian Pacific has been involved in a diluent recovery unit project (DRU) with energy and logistics companies. The DRU project turns heavy crude into a proprietary product called DRUbit that is formulated to be safer for rail transport.

Should an investor be concerned these companies are not only not shying away from coal or oil, but in the case of oil, they are actively innovating to deliver the product? It’s another dilemma, but this market reality of innovation and responding to challenges raises an interesting point. What if some of the other companies being excluded from ESG funds start cornering the market in the areas seen as solutions? What companies are currently building or acquiring some of the biggest electric vehicle charging networks in Europe?

Oil giants Shell, BP and Total.

These investments will only be comparatively small parts of their business, but the market is moving. Car makers have clearly flagged intentions to shift to electric vehicles and some governments have outlawed the sale of internal combustion engines by certain dates. This reflects the reality that markets adapt. Historically they have ruthlessly dealt with companies that no longer met market standards and expectations on a variety of issues.

Maybe it is the end of days for oil giants, or maybe they’ll successfully play a part in a transition to different energy sources?

As you can tell, ESG investing poses many questions and dilemmas. We certainly don’t have the answers, but if this is an area of interest, we think it’s definitely worth gathering as much information as possible, while also asking what type of investor you are? Are you an investor demanding change or you an investor looking to avoid certain products or industries? These won’t be the same things. Maybe there’s just too much grey here for you too even bother with it.

If you want absolute clarity on ESG investing, it will take some work to find it. If you want absolute purity on ESG investing, you’re unlikely to find it.