It’s no secret interest rates are low. Have ten grand in the bank? If you’re lucky with a ‘high interest’ account, at the end of the year you’ll have made $200. That’s before the tax man and inflation come calling. For those with a small amount who can’t get their head around the concept of risk, it’s dire straits.

We’re also told there are rough waters if you’ve got a few million. This from a recent article in The Australian (behind a paywall) by a financial adviser.

I recently met a new client — a divorcee with two teenage sons — who, on the face of things, ¬appeared to have no financial worries. She has $6.5m in total ¬assets, including a family home with no mortgage, and requires, she says, $120,000 a year to live on. Surely not a problem.

However, when we dug into her asset base, things were a lot different to what they appeared.

Her principal residence in inner Melbourne is unencumbered and valued at $1.5m. Her investment portfolio totals $5m, of which $3.5m is tied up in residential investment properties which, although they have appreciated in value, deliver little income. The remaining $1.5m is spread across equities and fixed interest, which average a yield of about 4 per cent per annum, producing $56,000.

The piece later notes her total income from investments was $70,000. So only $14,000 was generated by $3.5 million in residential real estate.

Unfortunately, the debt status of the residential properties wasn’t mentioned. To receive only $14,000 from $3.5 million in real estate suggests either a valuation error or unmentioned debts eating a chunk of cash flow. Even without the full picture, throw in land tax, water, council rates, insurance, agent rental fees, body corporate (if apartment) along with maintenance. Easy to see why residential real estate isn’t a cashflow proposition.

Wild valuations have seen real estate yields on the canvas. Due to favourable policy, residential real estate in Australia has become a low yielding speculative asset class that is mostly good for growth. Heading towards retirement or requiring cashflow? Next to useless. If you need to eat there’s no selling off a bedroom. The whole pile of bricks needs to be liquidated.

The adviser noted his recommendation was to part with the residential properties, which the lady was loathe to do. People get attached to stuff. A reason why financial advice is about behaviour. People want solutions that sit within the walls they’ve already built in their mind. Sometimes they need to let go. If successful with the recommendation the adviser was off to pick dividend stocks to bridge the income gap.

Sigh. Yes, sell off an undiversified real estate portfolio to put it into an undiversified share portfolio.

James Kirby, Wealth editor at The Australian, then wrote a column (paywalled again) off the back of this scenario. Kirby began hyperventilating that someone with $5 million could no longer meet their needs ‘risk free’.

… a remarkable scenario — despite having money in cash, property and the sharemarket the $5m gives his client a total income of $70,000! That is, for every $1m at risk out in the investment market, she gets about $14,000… that poor return for his client still requires risk… A casual observer might say it’s a bit rich to complain you can’t make enough money from such a portfolio: why not sell some assets and move on? It turns out she has no choice.

Return requires risk. Always has, always will. $120,000 is an ambitious income target, but not with $5 million dollars to potentially deliver it. Is the divorcee really in a serious quandary? Her big problem is terrible portfolio construction, not that interest rates aren’t higher.

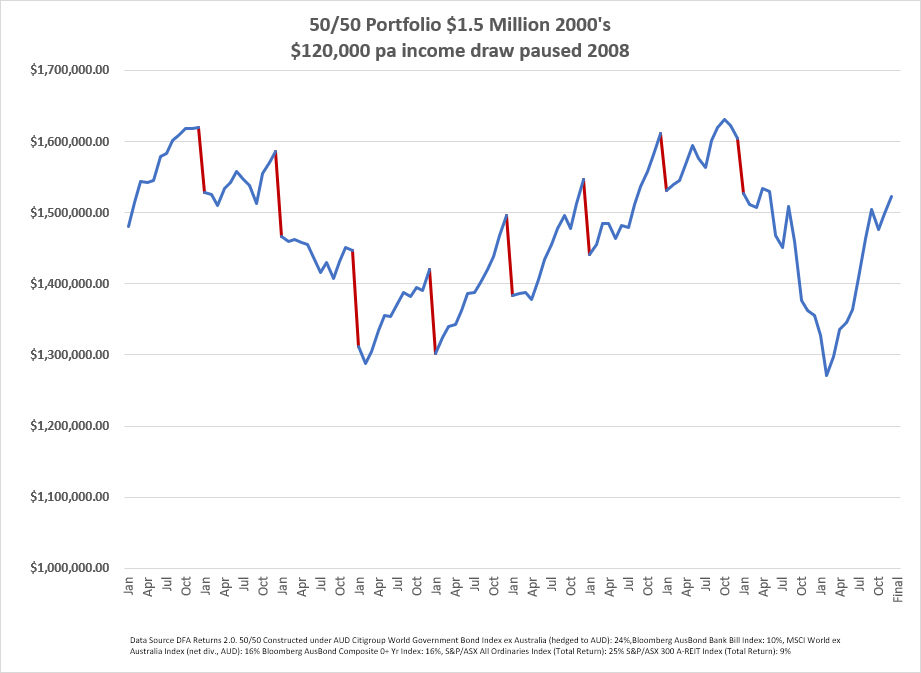

A history lesson. Using a 50/50 portfolio (half growth, half defensive assets) and her current liquid assets of $1.5 million. At the end of every year we’ll draw $120,000. The scenario takes no account of tax on the income draws or inflation.

First the 2000’s. Income draws are marked in red. The portfolio generally fluctuates in a range between $1.6 and $1.3 million, until the financial crisis where it hits a low of $1.04 million. The recovery took it to $1.25 million, before the final draw of $120,000 took it back to $1.134 million. Could be better, but throughout the time period a high-income demand is met while encountering a once in a lifetime financial crisis.

In the 2010’s the portfolio fared better. The portfolio balance generally remained between $1.4 and $1.6 million for the whole decade. After the final draw the balance was $1.423 million, not bad after pulling out $1.2 million in income.

As noted, the income demand for the size of this portfolio is large. Too large in reality. It’s flirting with danger. In the scenario noted the divorcee has another $3.5 million in equity. This raises a number of scenarios.

Liquidate some of the real estate and hold a cash reserve. In the event of a 2008 situation it gives the portfolio time to recover. As shown in this chart the v-shaped recovery after the crisis returns the portfolio slightly above its start value. If we follow the 2010’s from the previous chart it would continue to provide income throughout the next decade without much impact on the asset base.

However, that cash reserve is depleted some and if the divorcee doesn’t want to ever impact the asset base the portfolio will need to be larger to cope with market volatility.

If we double the portfolio to $3 million the outcome is much different. Both portfolios were able to better withstand market volatility due to their size vs the income requirements. Both finish each decade with a higher balance after drawing $1.2 million. The 2010’s portfolio asset base is up over 50% after the final draw.

Finally, only $3 million of the initial $5 million portfolio was used to achieve the income and retain plus grow the asset base.

This is a basic analysis as noted not accounting for other variables, but there are some conclusions to draw.

Advice is important. An adviser has the ability to model these scenarios to a greater level of detail accounting for tax, inflation and the structure of where the assets are held. When drawing the income, they’re better able to assess where to most efficiently draw the money from, taking account of capital gains discounts and franking credits if available.

Utilise assets that support your goals. If the goal is income, hold assets that produce income or can be liquidated in short order. No point agonising over the real estate. Especially if it did its job and made money. You may love it, but it doesn’t love you back. Holding off because the newspaper said the real estate market will go up this year? You can’t eat your shoes while you wait.

Be Realistic. Financial markets have proven incredibly resilient in providing returns to investors over long time frames, but they can’t work miracles. Best to understand what a portfolio is likely to withstand and what income draws it can safely handle. As we’ve seen $120,000 a year looks pretty good from three million, but at $1.5 million it begins to struggle.

No dilemma for millionaires. They’ll be just fine.