How far do we get without commitment and perseverance? Any task we begin in life is going to require some commitment and perseverance if we wish to pursue it thoroughly. That commitment may begin early in life. As children, we may show an interest to pursue a particular sport or hobby, alternatively our parents may force us into various activities they think we should pursue!

How long any of these endeavours will last, largely depends on whether we find them fulfilling in some way or how much persistence we have. As children, we can be fickle. Toys can fly out of the cot over the slightest thing. We lack any real experience. Our inability to rationalise time or where resources come from, allow us to get away with being fickle. As a child we may well give something up at a moment’s notice or not find ourselves sufficiently motivated.

That luxury of having support provided for by parents instead of having to sweep chimneys for our keep is particularly valuable before we’re in the real world. It provides a platform to determine what we’d like to dedicate our time to. Hopefully a task rewarding enough in some way to remain motivated for.

The longer we are in the tooth, the less fickle we can afford to be. Commitment and perseverance become more important in achieving goals – as long as we’re actually on the right path. In the 2016 book, Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance, author Angela Duckworth challenges the idea that it’s talent that propels us towards success in life. Instead of talent, it’s grit that’s the most reliable predictor of success.

Duckworth developed her own questionnaire that measured this intangible thing called grit. Her questionnaire reliably predicted things such as who might graduate from West Point military academy, or the which competitors would get the furthest during the US National Spelling Bee.

What exactly was grit?

First, these exemplars were unusually resilient and hardworking. Second, they knew in a very, very deep way what it was they wanted. They not only had determination, they had direction.

And:

skipping around from one kind of pursuit to another—from one skill set to an entirely different one—that’s not what gritty people do.

When we’re investing, it’s no different. The primary hurdle is settling on an investment philosophy. Importantly, one that works and has evidence behind it. The second thing is sticking with it.

Investing is nothing to do with talent, nor are gains just handed out for making an appearance on the first day. You also don’t get the choice of when you show up to collect the gains before leaving again. If only it was that easy. No one can predict when they’ll appear – so it’s important that an investor be prepared to commit to a long-term endeavour and have the persistence to ride out all types of markets.

Often some of the best gains will come in short spurts, as the following chart shows. Take away the best day on the ASX 300 between 2001-2017 and the average annual return over that timeframe falls 0.35%. Take away the best five days between 2001-2017 and the average annual return falls 1.61%.

As the chart shows, if an investor starts with $1,000 in 2001, by 2017 they’ve left behind over $800 if they missed those best five days. That doesn’t seem a huge amount, but start with $100,000 and then it’s over $80,000 left on the plate. The ability to commit to the process and persevere provides rewards, you just don’t know when they’ll appear – that’s why perseverance is required.

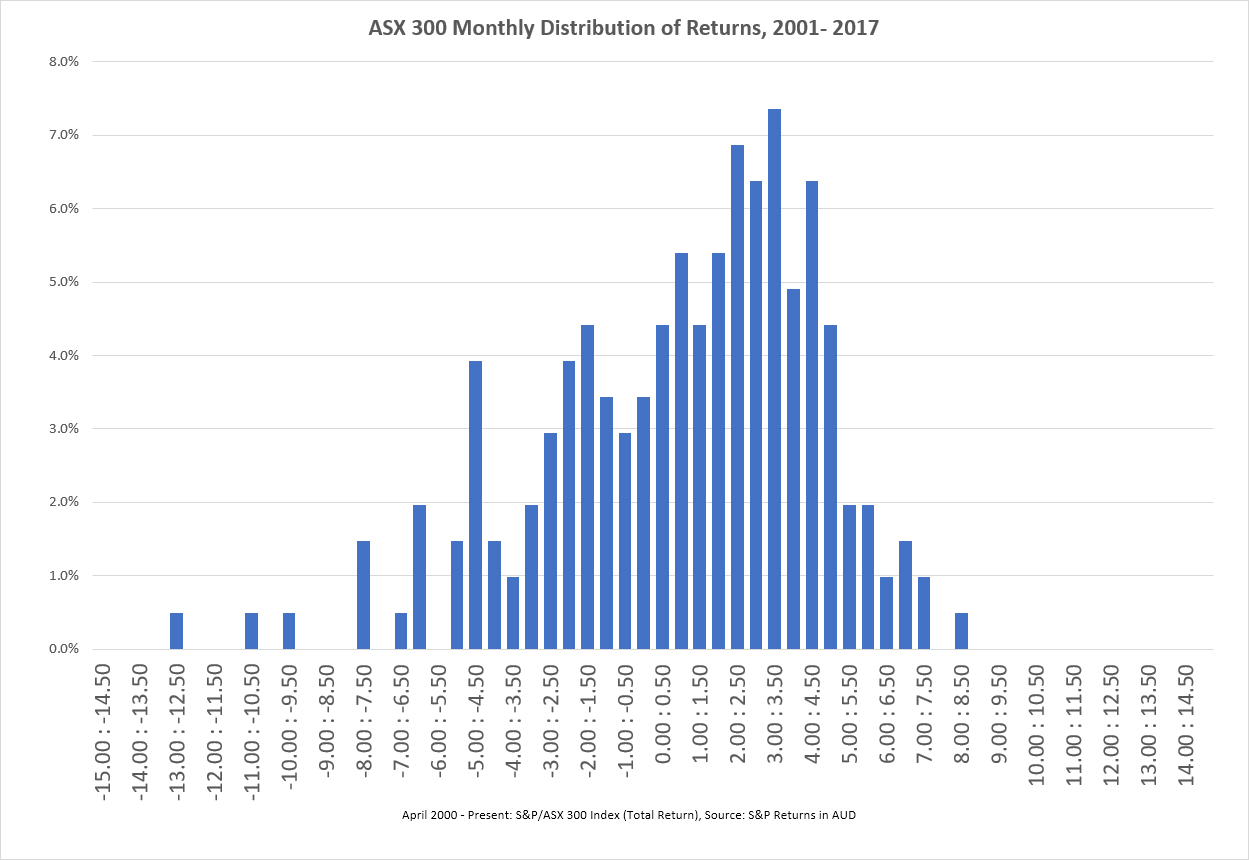

When we look at returns on a monthly basis over the same time frame, we find that the majority of months are positive. Over 63% of the time, but there are some concerning outliers to the left.

As you might expect, those three worst months came during the financial crisis. It’s never pleasant to see those sorts of declines are possible and it’s even less pleasant to experience them, but it’s important to acknowledge and understand they happen. It’s doubly important to understand they’re not fatal. The investors who doubted there would ever be a recovery after 2008 eventually lost their nerve and crystallised their loss at the worst possible time. When an investor encounters these periods, it is beneficial they have the grit required to emerge out the other side. It’s also important they understand their portfolio isn’t just their local equity index, holding a diversified portfolio means these months are never that extreme.

Is there anything else to be learned from the distributions of monthly returns? Well, some of the worst losses tend to cluster. There are sixteen instances of two or more consecutive negative months and six instances of three or more consecutive negative months. Is this an indicator of anything? Can you turn your mind to predicting the bad stretches, extending perseverance and grit to figuring out when to get out of the market ahead of the declines?

It would be folly to try. The last month of 2002 and the first two months of 2003 were all negative, surely that was the beginning of something bad? No, over the next 23 months, only three were negative. Or there was the last two months of 2011 which were negative. Maybe that would be the start of a bad run? Wrong again. There was only one negative month in the next fourteen.

As the old saying goes, “it’s time in the market, not timing the market that counts”. The gains are there, but it takes grit and perseverance to endure the declines, the volatility and the sometimes months of mundane sideways movement that will test an investor’s resolve.